Overview

Creatine is an amino acid located mostly in the body’s muscles, as well as in the brain. The liver, pancreas, and kidneys make about 1 gram of creatine a day. Supplementation enhances muscular energy, mass, and performance, and boosts exercise intensity. It may also boost brain function and fight certain neurological diseases.

Key Benefits

- Boosts high-intensity athletic performance

- It helps build muscle mass.

- Supports resistance to fatigue

- Improves recovery from exercise

- May decrease blood glucose levels

- It increases dopamine and mitochondrial function.

- It may reduce fatigue.

- Improves memory and recall.

- Aids in the production of adenosine triphosphate (ATP)

- It may protect against neurological disorders.

- May offer anti-aging effects on the skin

History of Usage

The French philosopher and scientist Michel Eugene Chevreul Creatine discovered creatine in 1832 by extracting it from meat. He called it creatine in homage to the Greek word kreas, which means meat. In 1912, Harvard researchers found that ingesting creatine could boost the creatine content within muscles. In 1923, new findings suggested that the use of oral creatine in animals promoted nitrogen retention. This meant that more protein was building up in the muscles, which contributed to weight gain. Later that year, Alfred Chanutin gave 10g of creatine a day for one week to humans. He concluded that this increased creatine storage in muscles. It wasn’t until the 1950s that creatine was manufactured in a laboratory. In 1975, the previous scientific findings were verified: creatine use resulted in faster muscle recovery, increased protein in the muscles, and increased performance.

Creatine is increasingly being used by amateur, collegiate, and professional athletes. It is one of the most popular sports dietary supplements on the market, with more than $400 million in annual sales.

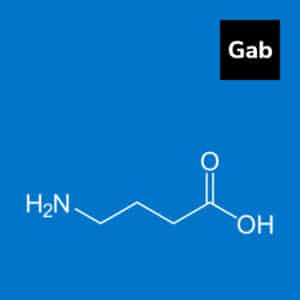

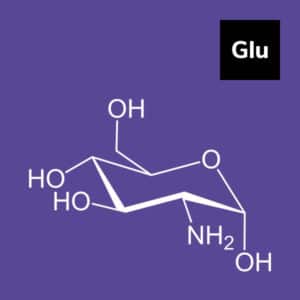

Biochemistry

Around 95% of the body’s creatine is kept in the form of phosphocreatine in the muscles. The remaining 5% is located in the brain, kidneys, and liver. Creatine supplementation raises phosphocreatine levels, which aids the body in producing more ATP.

The majority of creatine production occurs in the liver, and the first step involves the enzyme glycine transaminidase transferring an amidine group from arginine to glycine. The resultant guanidinoacetic acid is methylated to create creatine by guanidinoacetate methyltransferase (the methyl group is derived from S-adenosylmethionine).

The creatine is subsequently carried through the bloodstream to storage locations in skeletal muscle, where it is phosphorylated by ATP to generate creatine phosphate. Additionally, dietary creatine is delivered from the GI tract to the proper storage sites. Around 60%–70% of the creatine in skeletal muscle is phosphorylated, preventing the molecule from migrating across the plasma membrane and effectively trapping it within the muscle cell.

Creatine breakdown produces just creatinine, which diffuses into the bloodstream from the muscle. Creatinine is filtered in the glomerulus and eliminated in the urine upon entrance into the renal parenchyma.

Due to the fact that creatine is contained in meat, vegans frequently have low levels. Creatine pills and monohydrate can be used safely and effectively by athletes, body builders, recreational users, and enthusiasts in the public. Long-term use, on the other hand, may have certain detrimental consequences on the cardiovascular and renal systems.

Recent Trends

The global creatine market was worth $452.4 million in 2020 and is expected to reach $641.7 million in 2027, rising at a 6.0 percent compound annual growth rate between 2021 and 2027. Due to advanced manufacturing technologies and increasing economic development, the United States of America, China, and Europe continue to be the primary regions that consume creatine.

The most recent trend in creatine supplements is the incorporation of creatine with nitrate. This may somewhat boost absorption and supplement the typical effects of creatine monohydrate with increased blood flow and muscle “pump” (swelling).

Creatine is available in powder, tablet, and capsule form and is also available in a vegan form.

Precautions

- Women who are pregnant or breastfeeding should visit a healthcare practitioner prior to consuming creatine.

- Before using creatine, those with a chronic ailment such as heart disease or cancer should visit a healthcare practitioner.

- Caffeine consumption may reduce creatine’s potency.

- The use of creatine in conjunction with a daily caffeine intake of more than 300 mg may exacerbate the progression of Parkinson’s disease.

- Creatine should not be used by athletes who have pre-existing kidney disease or are at risk of developing kidney dysfunction.

- Cyclosporine, aminoglycosides, gentamicin, tobramycin, and anti-inflammatory drugs such as ibuprofen are just a few of the medications that may interact with creatine.

References

- Persky AM, Brazeau GA. Clinical pharmacology of the dietary supplement creatine monohydrate. Pharmacol Rev. 2001 Jun;53(2):161-76. PMID: 11356982.

- Sakellaris G, Nasis G, Kotsiou M, Tamiolaki M, Charissis G, Evangeliou A. Prevention of traumatic headache, dizziness and fatigue with creatine administration. A pilot study. Acta Paediatr. 2008 Jan;97(1):31-4. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2007.00529.x. Epub 2007 Dec 3. PMID: 18053002; PMCID: PMC2583396.

- Balsom PD, Söderlund K, Sjödin B, Ekblom B. Skeletal muscle metabolism during short duration high-intensity exercise: influence of creatine supplementation. Acta Physiol Scand. 1995 Jul;154(3):303-10. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1995.tb09914.x. PMID: 7572228.

- Branch JD. Effect of creatine supplementation on body composition and performance: a meta-analysis. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2003 Jun;13(2):198-226. doi: 10.1123/ijsnem.13.2.198. PMID: 12945830.

- Tarnopolsky MA, Beal MF. Potential for creatine and other therapies targeting cellular energy dysfunction in neurological disorders. Ann Neurol. 2001 May;49(5):561-74. PMID: 11357946.

- Davani-Davari D, Karimzadeh I, Ezzatzadegan-Jahromi S, Sagheb MM. Potential Adverse Effects of Creatine Supplement on the Kidney in Athletes and Bodybuilders. Iran J Kidney Dis. 2018 Oct;12(5):253-260. PMID: 30367015.